Hope diamond : A blue diamond’s cursed odyssey

- lucilledaver1

- Feb 27, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: May 15, 2024

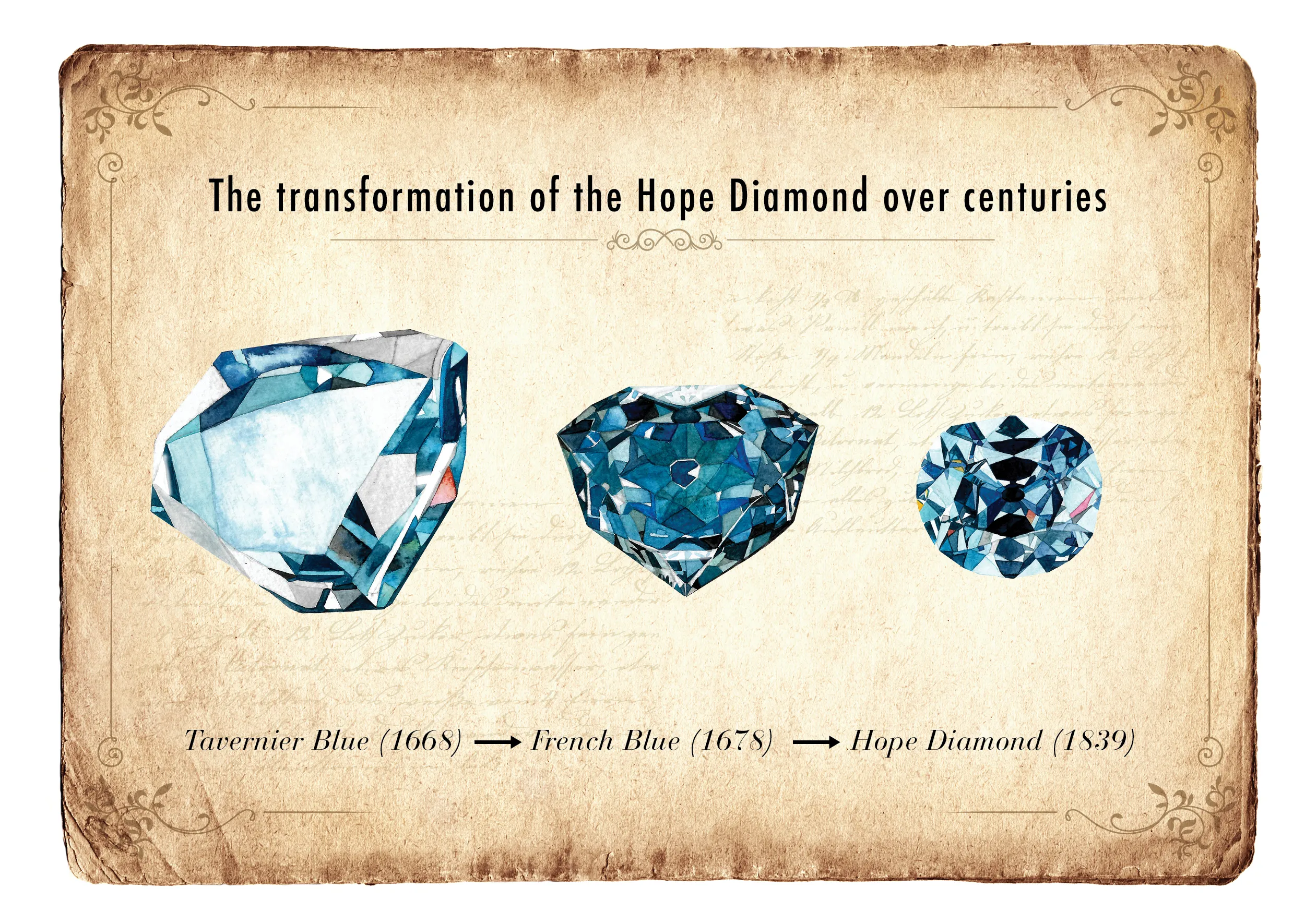

Graded by GIA in 1988 and 1996, the famous Hope Diamond (also known as Bleu Tavernier and Bleu de France) is a brilliant 45.52 carat antique cushion cut, a fancy deep blue grey of VS1 clarity. This exceptional gem has stood the test of time, leaving in its wake a legacy as exceptional as its luster. From its mysterious discovery in India to its status as an icon on display, this diamond has crossed centuries of history, carrying with it legends and intriguing tales.

Blue diamonds: a chemical wonder

Blue diamonds are very rare. Their blue colour, due to the infinitesimal amount of boron atoms in their crystal structure (type IIb in diamond classification), can range from very pale to very deep. Another characteristic of these diamonds is their very pronounced red phosphorescence when exposed to ultraviolet light.

Blue diamonds constitute only ≤0.02 per cent of the diamonds extracted worldwide. They’re only found in South Africa (Cullinan Mine), Botswana (Orapa and Karowe mines) and India (Kollur Mine). Among these 0.02 per cent, only one per cent are as deep blue as the Hope Diamond.

The initial adventure: Jean-Baptiste Tavernier

The Hope Diamond’s story begins in 1642, when French merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier set off to Asia. In India, he acquired a collection of several thousand gems, one of which was an exceptional 115 carat rough diamond with a violet-blue hue. The diamond was soon named the Bleu Tavernier.

At the time, India was the world’s leading supplier of diamonds, and the discovery of exceptional gems was no rarity. While the exact date of the diamond’s discovery remains uncertain, it is estimated to have been extracted from the Kollur Mine in the early 1600s.

The Sun King and revolution

In 1673, King Louis XIV of France fell under the spell of the diamond, buying it along with 47 other large diamonds in exchange for a noble title and a tonne of gold. Renamed the Crown Blue Diamond or Bleu de France, the stone was cut by Jean Pittan, the court’s official jeweller—reducing its weight to 69 carats. A masterpiece of French Baroque lapidary art with 72 facets and 7th-order symmetry, the diamond features a central rose. It became the focal jewel in the Golden Fleece brooch, embodying the grandeur and opulence of the French monarchy at the time. A masterpiece of Rococo goldsmithing, the Golden Fleece also included: a pale blue diamond weighing 32.62 carats, four diamonds weighing four to five carats, 478 smaller diamonds (some of which were painted yellow and red), a spinel weighing 107.88 carats, and three yellow sapphires.

Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette eventually inherited the Golden Fleece, but in 1789, the French Revolution brought their reign to a bloody end. In 1792, the royal treasury was confiscated by revolutionaries and the Bleu de France was listed amongst the stolen jewels. After this theft, the jewel disappeared for two decades, leaving behind a veil of mystery. From this event, rumours of a curse emerged, claiming that anyone in possession of the stone would be condemned to misfortune.

Louis the 14th and the golden fleece. Smithsonian institute and French natural History museum

The enigma: two diamonds

The 19th century marked the return, or rather the arrival, of the Hope Diamond to the world stage. In 1812, a 45.5 carat cushion-cut deep blue diamond appeared in London, two days after the 20-year statute of limitations for theft in France had expired. It was bought by King George IV, and resold when the British sovereign died in 1830. Later acquired by London banker Lord Henry Philip Hope, it was renamed the Hope Diamond.

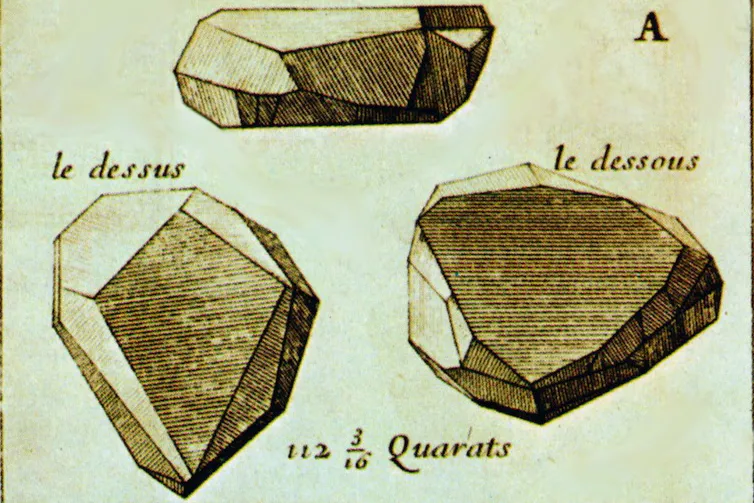

Speculation about the connection between the Hope Diamond and the Bleu de France diamond lost during the French Revolution was rife. The most notable theorist was jeweller Charles Barbot. In 1856, Barbot compared the diamonds based on two imprecise engravings by Lucien Hirtz—the only known representation of the Bleu de France at the time—in the work by historian Germain Bapst. Speculation was not confirmed until 2007, when a lead model of the Hope Diamond’s 45-carat cut was discovered at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris. Realistic replicas of the original diamonds and computer models confirmed the transformation of the Hope Diamond from the Bleu de France. Further research in the museum’s archives uncovered documents saying, “a certain Charles Achard, donor of the lead [to the museum] and jeweller in Paris, left an indication that the French diamond had been owned by his client ‘Mr. Hoppe of London.’”

Drawing of the different cut of the hope diamond. Smithsonian institute and French natural History museum

Successive owners and a curse

The Hope Diamond remained in the Hope family until the early 1900s, when Lord Francis Hope sold it to cover his debts. It changed owners several times since, passing through the hands of private collectors and renowned jewellers until it reached Cartier in 1910.

The following year, American heiress Evalyn Walsh McLean received it as a gift from her husband Edward Beale McLean, owner of The Washington Post. The jewel was set in a necklace by Pierre Cartier. Despite its reputation as a cursed diamond, McLean succumbed to the stone’s charm, buying it with a replacement clause in case of misfortune. To allay the couple’s fears, Pierre Cartier agreed to exchange the diamond for jewels of equivalent value if Evalyn or her husband died within six months.

The Washington Post published an article entitled “Hope Diamond has brought trouble to all who have owned it” in 1908, followed by another in 1911 containing a list of the supposed victims of the curse. The curse eventually caught up with the new owner: her son was killed in a car accident, her daughter died of an overdose, and her alcoholic husband left her for another woman and ended his life in a psychiatric hospital. Evalyn McLean died of pneumonia at the age of 60 in 1947.

American conquest: The Hope Diamond at the Smithsonian

Two years after McLean’s death, jeweller Harry Winston acquired her entire jewellery collection, including the famous blue gem. In 1958, he donated it to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. To make the transport of the Hope Diamond as discreet and secure as possible, Winston sent it to the Smithsonian by post in a simple kraft envelope, creating a false trail for journalists.

Since then, this rare beauty has been exhibited for the whole world to see, putting an end to the halo of misfortune that once surrounded it. Estimated at C$464 million, the Hope Diamond continues to fascinate, attracting millions of visitors every year.

By Lucille Daver for Jewellery Business magazine (Canada):

References

Brickell, F. C. (2019). The Cartiers: The untold story of the family behind the jewelry empire. Ballantine Books.

Crowningshield, R. (1989). Grading the Hope diamond. Gems & Gemology, 25(2), 91-94.

Daver, L., Bureau, H., Boulard, É., Gaillou, É., Cartigny, P., Pinti, D. L., ... & Baptiste, B. (2022). From the lithosphere to the lower mantle: An aqueous-rich metal-bearing growth environment to form type IIb blue diamonds. Chemical Geology, 613, 121163.

Farges, F., Sucher, S., Horovitz, H., & Fourcault, J. M. (2009). The French Blue and the Hope: New data from the discovery of a historical lead cast. Gems & Gemology, 45(1), 4-19.

Kurin, R. (2017). Hope Diamond: the legendary history of a cursed gem. Smithsonian Institution.

Larson, B. (2021). The Smithsonian National Gem Collection—Unearthed: Surprising Stories Behind the Jewels. The Journal of Gemmology, 37(8), 867-868.

Ogden, J. M. (2018). Out of the Blue: The Hope Diamond in London. Journal of Gemmology, 36(4).

Comentarios